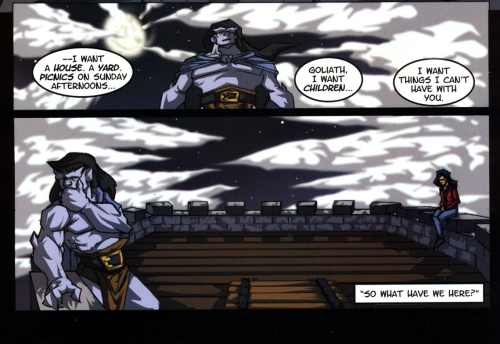

mimeparadox:musashden:Did this bit– Did Eliza seriously just break up with Goliath because she

mimeparadox:musashden:Did this bit– Did Eliza seriously just break up with Goliath because she turned into a basic bitch over night???Honey, adopt a kid and get a place on Long Island - you don’t tell this dude to see other people when there are only two female gargoyles currently alive and one of them is his daughter. The Quarrymen are currently hunting his kind - he can’t exactly meet a new chick in da club.This bitch. WTF.… Can you tell I don’t like comic book Elisa. Seriously what did they do to her? This is some lame shit right here.Yo brother is a flying cat. You spent last summer on a magic boat. Yo partner is in the gottdamn Illuminati and you want ‘normalcy’??? Bitch please. I am utterly convinced that Greg Weisman is someone who really needs restrictions and feedback in order to rein in his more frustrating tendencies and do his best work. Young Justice season 3 is a disaster, and this is just baffling. I mean, why? How? Why? Normally I’m all for “fuck the audience; do whatever you want,” but here’s I just have to wonder: who wanted this? People had been waiting for a decade for some sort of continuation to the story ending in “The Journey,” and to see the pay-off to Goliath and Elisa finally getting together, and this is the first thing you think of doing? I mean, I can’t even imagine it being enjoyable to write–it’s not clever, it’s not complicated; it’s just a bog standard breakup applied to characters for whom it does not work at all. While it doesn’t actually feel out of step with his other work–there’s some very suggestive, if dismaying, patterns when it comes to his female characters–it still manages to feel baffling.Is there no circumstance under which Elisa would break up with Goliath? Far from it. Absolutely none of them apply here, not given what we’ve seen after “Hunter’s Moon”–which, according to the timeline, takes place less than a week before this scene. All of the things she references here, while very good reasons not to be with someone, are all factors that existed before “Hunter’s Moon”, and are things which she would have undoubtedly considered before pashing Goliath. What’s more, there’s no change in circumstances that we see that would have led her to reconsider. The only way this works is if we reimagine the kiss not as the conclusion of months of thinking, but rather, as something she did on a whim, and is only now thinking about. And that’s not Elisa. Also not Elisa: someone who wants the fifties’ American Dream existence. I mean, she could, and that would be fine, but at no point in the series do we ever see that that sort of existence is something that interests her–not unless she’s far better at compartmentalizing than we’ve ever seen her be. If this is something she wanted, it would have become apparent long before this point–say, during her months- long, seemingly interminable world tour, immediately afterwards (it would have made perfect sense for Elisa to decide that she needed a good long break from gargoyle weirdness after returning to New York), or even immediately before kissing Goliath. These specific issues feel less like an Elisa problem and more of Weisman thing–people have noted similar odd beats in shows like Young Justice.It’s worth noting that by the end of this arc, Elisa is back together with Goliath, and while them being together is theoretically better than them being apart, the damage has been done. Not only do we not really get to see Goliath and Elisa as a couple for the rest of the comic book series, her dithering in both directions–none of the issues raised here have been resolved–are enough to really put a dent in Elisa’s characterization, and result in her at her worst. It’s the last thing the audience wanted or needed, after a decade’s absence. Having been frustrated with YJ: Outsiders and since gifted with some terribly cursed knowledge from friends in the Magic the Gathering fan community, I’m going to agree with @mimeparadox on this being a Weisman thing. It turns out that, between the release of YJ: Outsiders and YJ: Phantoms, Weisman seemingly lost a contract with Wizards of the Coast, the publisher issuing an apology and cancelling plans for a future book amidst massive critical backlash over bigoted writing in his War of the Spark novels.And, having had a quick gander (thanks I guess to my MtG buddies for providing summaries, articles, videos and excerpts), the ongoing patterns that emerge are… concerning to say the least.Narratively, War of the Spark: Forsaken shows many of the same symptoms; failure to focus on or conclude the stories of central characters, misrepresentation/contradiction of established characterisation, overuse of telling instead of proper set-up or development, and a generally fragmented story flow.The novel was also criticised for less than progressive writing across the board, including insensitive handling of both real and fictitious minorities, incredibly binary/ traditionalist depictions of gender and gender roles, uncomfortable treatment of consent and boundaries - especially from telepathic characters (closely mirroring issues with Young Justice’s writing of SuperMartian) - and being worryingly casual about the implications of another telepath having non-sexually groomed a sixteen-year-old girl since she was a baby fucking really, Greg? but the two that especially raised flags for me were:War of the Spark: Forsaken contains another instance of Weisman actively de-fanging a previously strong female character upon assuming creative control. This is the same thing we see with Elisa above, and it also happened to Young Justice’s Artemis Crock. Under Weisman’s majority control in YJ: Outsiders, Artemis is written to have completely fallen apart after the death her boyfriend, falling into the arms of her brother-in-law Red Arrow (a set-up that comes at a massive opportunity cost for her, Red Arrow and her sister Jade’s characterisation), being narratively pressured to settle down with Red Arrow and co-parent her niece in Jade’s absence, and given a grief scene that ignores her and Wally’s existing characterisation/ conflicts in favour of emphasising a heretofore undisclosed desire to fully give up heroism for a life of traditional domesticity as Wally’s wife and child-mother. (The grief hallucination also features a moment where Artemis is made to fantasise about being heavily pregnant with Wally’s child - one of several instances where Outsiders seems uncomfortably fixated on physically presenting women as pregnant/ maternal - made more uncomfortable by how personally uninvested/ unprepared both she and Wally seem as it’s happening.)Something similar happens in Weisman’s writing of Liliana Vess. Liliana is one of the longest-running characters in the MtG canon, previously characterised as a functionally-immortal and extremely powerful (bordering on God-level) necromancer and healer; pragmatic, cunning, self-preserving, morally ambiguous (although care for her allies had shifted her more towards good), being generally in control of whatever situation/ relationship she was in, and having a fairly detached/ composed response to the deaths of even family and close friends/ lovers. Weisman’s Liliana Vess, meanwhile, is written to be emotionally shattered, lost and heartbroken with grief over the death of Gideon (a character who Weisman writes to be obsessively praised by multiple women - including Liliana herself - as the manly masculine true hero of the battle, despite Liliana being the actual strategic linchpin and Gideon’s needless self-sacrifice causing most of the problems she faces in Forsaken) to the point that she attempts suicide, only regaining her will to live and sense of purpose after hallucinating him standing over her. By the end of Forsaken, Liliana has departed for another world, assuming a new identity that just-so-happens to share a surname with Gideon’s family. This conclusion to Liliana’s arc was unpopular (to the point that the publishers later allowed it to be retconned out) but the thing that Weisman drew the heaviest fire for - and is most indicative of these patterns - was his offensive mistreatment of AFAB queer characters.For three years leading up to War of the Spark, previous writers for the franchise had been building well-received romantic chemistry between female planeswalkers Chandra Nalaar and Nissa Revane, the “Gruulfriends” being a fandom darling with many speculating that they would become an official couple. And then Weisman writes this:Chandra had never been into girls. Her crushes - and she’d had her fair share - were mostly the brawny (and decidedly male) types like Gids. But there had always been something about Nissa Revane specifically, something the two of them shared in that great chemical mix - arching between them like one of Ral Zarek’s lightning bolts - that had thrilled her. From the moment they first met.Now everything’s different.It was over. Before it ever had a chance to begin.- Greg Weisman, War of the Spark: Forsaken…they had admitted to each other that they loved. But both of them knew deep down they were only speaking platonically.- Greg Weisman, War of the Spark: ForsakenNow, to be fair, ending Chandra and Nissa’s relationship may not have been Weisman’s call. My understanding of how this works is that major plot points, specific arcs and general trajectories are mandated by the MtG creative team, following the corresponding card set, with the writer commissioned to weave them into a narrative. However, the decision of how to execute on those mandates, how the dots are connected and how blank spaces are filled are largely left to the discretion of the writer. And what Weisman chose was to not only scrub any suggested queerness from the character, but to actively retcon it to have never existed at all and forcibly instate a heteropatriarchal binary by emphasising that not only is Chandra entirely straight, she exclusively prefers decidedly male and masculine men. It’s just so revealing of how Weisman views gender, sexuality and women and, when combined with the other patterns, suggestive of a deeply insecure toxic masculinity.And this pattern tracks with YJ: Outsiders botched treatment of AFAB queer characters. The handling of Halo was criticised for multiple reasons, including:Halo is disproportionately made the object of violence, the show giving them a passive revival/ healing superpower that is used to justify arbitrarily killing/ injuring them for gore/ shock value on multiple distinct occasions. As Halo is an intersectional minority, this plays into well-criticised tropes of using and trivialising violence towards feminine/ queer/ non-white characters for spectacle.The presentation of Halo’s bisexuality is directly linked to irresponsibility/ infidelity (a common Biphobic stereotype). Halo and female classmate Harper sneak out to shoot stolen guns and drink underage before kissing, stopping to explicitly acknowledge that they both have heterosexual boyfriends, and then continuing to kiss. Then, in a later scene, Halo berates themself for being a bad partner.Halo is suggested to be genderqueer in Outsiders, with some lines indicating they do not feel fully female. However, Halo is more commonly made to express sentiments that something is “wrong with” or “broken inside” them - with a reveal towards the end of the show that Halo is actually a human girl’s corpse being reanimated by a robotic alien consciousness and direct dialogue implying that it is the robot’s inability to understand gender that causes Halo’s discomfort. Not only does this play into well-criticised tropes of presenting queerness as inhuman/ an abomination, it should be noted that the specific idea of AFAB trans/ nonbinary people being ‘damaged cis-girls confused by an unnatural influence’ mirrors a common piece of real-life anti-trans rhetoric.The reveal above also creates a deeply unfortunate implication that Halo - whose wearing of a Hijab codes them as one of the most prominent culturally non-Christian protagonists - does not have a human soul.Again, in fairness, some of this could be inherited issues from the source material. Comics!Halo is also an alien consciousness resurrecting a human body, there have been storylines where the character is killed and in some way resurrected via their powers, and the Harper Row of the comics is also bisexual. However, Halo’s powers, ethnicity, culture/religion, sexuality and gender identity were actively changed in adaption by Weisman and his team (the Halo of the comics most commonly being a white woman who was typically heterosexual and possessed by a different kind of alien) and the choices made in their execution and presentation end up baking well-criticised racist, biphobic and transphobic tropes into this iteration of the character. While not erasure, Halo’s queerness (and therefore deviation from cisheteropatriarchal expectations) is consistently presented as something negative/ abnormal (either actively or by implication), and the repeated violence they are subjected to could be read as punishing their existence in a Motion Picture Production Code-adjacent way.I also want to briefly touch on Weisman’s handling of queer men which, while better, still isn’t exactly great. Despite being primary characters in their main seasons, Kaldur and Bart’s respective relationships in Outsiders are noticeably minimised outside of a handful of specific frames - something that becomes more conspicuous when considering how willing the season is to give innuendo, kisses, pregnancies and fully-animated post-coital scenes to even secondary cishet couples, and that Kaldur’s romantic feelings had been an ongoing character beat referenced across Season 1, Season 2, the videogame and the companion comics when it was directed at a woman. There’s also something a bit more… insidious. While Ral and Tomik’s relationship in War of the Spark is mostly positive, Forsaken also directly accuses Ral of treating his homosexuality as a free-pass to be misogynistic (seemingly the only time Forsaken acknowledges the sexism in its writing). And in the same vein, you have to wonder: of all the unnamed background characters in the Young Justice companion comics, why did Weisman and his team pick an unredeemed member of the pro-ethnic-genocide racial supremacy cult to be Kaldur’s token boyfriend?Taken as a whole, these patterns are very difficult to interpret in good faith. Some of them could be missteps or oversights, but there are enough for it to become suspicious. And others are so obviously out of place that they could only appear in the narrative as the result of active choice. At best it indicates a wilfully privileged ignorance and a basic failure of compassion in not considering how audience members who identified with these characters would be made to feel when seeing them treated this way. (An odd choice for someone who so vocally likes to claim allyship on social media.)Now, Weisman did respond to the criticism over Chandra and Halo, but those responses leave something to be desired. With Halo, his most common defence seems to be a claim that audiences were misinterpreting/ misunderstanding the character’s “journey”, which is 1. a bit distasteful since it basically attempts to speak over the feelings/ experiences of actual minorities, and 2. sort of a tacit admission of failure in another direction since the primary job of a writer is to communicate understandably. Weisman’s statement on Chandra claims that he had a different original vision that became lost/ distorted through miscommunication with the editors/ publisher, which seems a bit suspect when considering that 1. he doesn’t elaborate on what that alleged original plan was, 2. similar patterns appear in his other works, 3. the same publishers had - presumably - been approving the previous three years of writing, 4. statements from MtG’s story R&D team suggest that Chandra was always conceived as a queer character (and she has since been written to again show interest in women) and 5. again, professional communicator.But let’s interrogate that claim of editorial interference a little further, because what we have here is a three-franchise litmus test. Disney, DC Comics and Wizards of the Coast are separate media entities, who shouldn’t have any significant overlap in their editorial teams, and yet we see common patterns emerge once Weisman takes creative control of a story as lead writer. So what’s more likely? That Weisman is the victim of a multi-franchise conspiracy, where three independent publishers/ editors have forced revisions and/or made changes behind his back until his “original intent” was overrun by narratively broken, insensitive prejudice? OR that Weisman is the common factor, that these publishers - trusting in his resume and reputation (which is increasingly looking like the product of lucking onto teams with more skilled co-writers who could elevate his better ideas and more skilled editors to provide restriction/ structure/ direction) - likely did not provide adequate creative supervision and/or time to course correct, and that the pattern that results reflects his own biases, creative weaknesses and sincerely held beliefs?Suffice to say, Greg Weisman is no longer a creator for whom I have any professional or personal respect. Because when I look across this collection and see emerging patterns of racial insensitivity, worrying patterns of abuse-normalisation, recurring instances of sexism and heteronormativity, both overt and insidious queerphobia, attempts to sidestep accountability for anything that can’t be passed off as an innocent accident, the casual disrespect towards previous writers/teams’ work in discarding continuity and characterisation, and the casual entitlement of expecting fans to independently source/ revise/ invent massive amounts of content to correct for those problems, well… I see Red. And I do mean that in all its clever implications. -- source link

#gargoyles comics#young justice#greg weisman#sexism cw#queerphobia cw#bigotry cw