Grey and Black ficby needsmoreresearchart by nisiedrawsstuff (This is to some extent a follow-up to

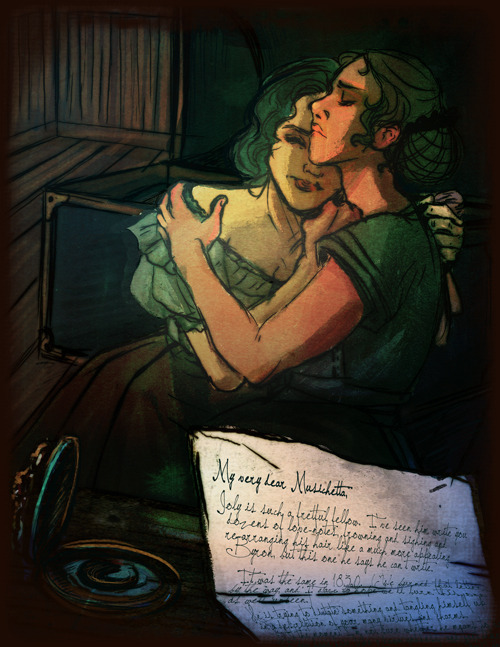

Grey and Black ficby needsmoreresearchart by nisiedrawsstuff (This is to some extent a follow-up to Your Wildly Devoted Joly (and also Lègle de Meaux, though it ought to stand on its own. Musichetta and Bahorel’s Laughing Mistress keep going.) —- Sophie was already in mourning: her mother had died early that spring. Black diminished her, Musichetta thought. Well—no, not diminished. But she did not laugh as much; she did not alarm anyone by matching a fuchsia dress with a lime green feathered bonnet. Her skin was only a few shades warmer than the black silk. Musichetta could not afford a full set of mourning clothes. Oh, Sophie would have lent her the money—given her the money—but it would have come out of the print-shop, and really it was the time that Musichetta couldn’t afford. Even so found a night and a day to alter her old grey dress. When she put it on she stared at herself in the mirror. Grey dress—grisette—black trim—a widowed grisette? Who ever heard of such a thing? She practiced a shrug. Practiced a chilling frown. She was neither a grisette nor a widow but still, she was something like both. —- (“Hush, your dress is perfect. If you fuss about it any more you’ll hurt my feelings. Yes, trust me, the sash should lie that way, it looks just right.” Musichetta shook her head impatiently. For a young woman whose knowledge of needlework ended at fixing lost buttons, and whose interest in fashion-plates was purely professional, Sophie was so reluctant to trust a friend who she knew understood much better about dresses. Left to her own devices she wore the most impossible colors. “And don’t even think about touching your hat. If you touch that hat, Sophie, if you shift that feather so much as one inch, so help me God I will—” “What about flowers?” Musichetta took a deep breath and let it out. “Yes. Yes, all right, you may have some flowers. We’ll just step into here—” The gallery was a regular spot for sellers of all the little trinkets and pretty things that men and women might pick up before meeting dear friends. Musichetta and Sophie wove through the crowd, stepping around young men picking out the perfect nosegay and young women choosing among the cheaper painted fans. Sophie couldn’t do anything too scandalous with flowers, could she? Musichetta let her attention wander: they were to meet their law-school friends today, to celebrate the failure of another term. Never a lawyer! read Sophie’s sash. She had insisted, and Musichetta had sat up all night at the embroidery-work. Her only demand in exchange was that Sophie let the end of her shawl fall over the words so that they were not immediately, confusingly obvious. What sort of a motto was that? Musichetta nodded absently while Sophie collected poppies, cornflowers, a single lily, and had them tied up in ribbons. If only she were taller— Of course it was silly to be standing on her toes and craning her neck. Bossuet and Bahorel would find them, or they would find Bossuet and Bahorel— Next to her, Sophie squeaked as someone spun her around and scooped her into an embrace. When Bahorel set her on her feet, he stared frankly and admiringly at her bosom. He bent down and kissed the petals of the flowers pinned just at the front of her dress. “My dear, that is a truly brilliant and most Republican bouquet. Someone will surely arrest you for that.”) —- “Maria Charpentier? Or—‘Musichetta?’” She had seen Joly’s brother once before. Not met, because that would imply introductions, but seen. Then he had come to take Joly away down to Avignon to recover from adventures with police. Now Musichetta lifted her chin, frowned, shrugged her shoulders back. Ready for battle. His hat was already off; he stepped up to the shop counter with an open hand to clasp hers. No smile. It would have looked strange with the deep mourning he wore. “I’m sorry to trouble you, Mademoiselle. May we speak a moment?” Vous, not tu. A courtesy. Sophie had come into the front of the shop, called by the jangle of the bell at the door. She put her hand on Musichetta’s shoulder. “You can use the office. I’ll keep the counter.” Musichetta had hoped for an excuse to refuse. In the office, she looked past her visitor’s shoulder at a map on the wall. He looked down at the glossy black hat perched on his knees. “I’ve been going through my brother’s rooms. There was a trunk marked with your name and this address. I thought I’d confirm that it was you before I brought it in?” She nodded. “…Very good. I, ah. I believe your family are from Avignon?” “Near there. My father was a greengrocer.” “Do you ever think of returning? Setting up a, a hat shop, or…?” “I prefer Paris.” She looked down at her hands, folded in her lap. Her guest looked past her shoulder at the bookshelf behind her. “If you are in any difficulties—” “I am not.” “—If any arise, here is my card. I am sure my brother would have wanted you to be—” “Thank you.” She had to look at him to take the card. His eyebrows were twisted up in concern; his face was marked with freckles and smallpox scars. Probably he was a kind person. Probably in other circumstances he didn’t speak so stiffly. Probably he meant his offer entirely sincerely. Musichetta resented her impulse to sympathize. - “He probably means you should ask him for money if you turn up pregnant.” Sophie knew how to deliver a verdict. “Has anyone from Bahorel’s family come up to Paris?” “No. His sister wrote. I didn’t realize she even knew my name. She asked more directly.” “If you were—?” “Right. But I’m not.” Musichetta did not think she was either. She had never yet been a tragic figure. —- Two of their printers were in prison, father and son. They had been in the fighting. Not at the—not at the barricade. At a more fortunate one, one with survivors, one where arrests were made. Musichetta tried not to resent this. She also tried not to listen to the voice that said Maybe it’s just as well. Men die in prison. They come back different. Their lovers have to give them up and be faithful, both at the same time. The dead, at least, are dead. Sophie said, “We’ll see what we can do for the family.” In the end, the younger brother came to work at the print shop. He was fourteen, stocky, near-sighted, serious; they could pay him at the rate they had paid his brother, who had had four years’ experience. The boy’s sister came too, a round-faced twelve-year-old girl. And so Sophie and Musichetta had a servant, at least in name. She stayed with them four nights a week, in the room that Sophie’s mother had slept in; Sophie and Musichetta still shared the loft over the printing room. What to do with her? Feed her, educate her, find out what she could do well. Musichetta had never been an employer. She had never been a mother either. It was hard to tell which was needed. One night, as they were getting ready for bed, Sophie said, “I see you’re teaching Jeannette to sew.” “Yes, she had never set a pair of shirtsleeves. It’s a good thing to know.” “If you sew shirts.” “Sewing shirts is a good thing to know.” “Hm. Take her into the shop tomorrow, and start her learning accounts?” Musichetta put down her hairbrush. “Oh, Sophie. Are you valuing the skills of the shopkeeper—the employer, the petit bourgeois—over those of the worker who produces goods with her own hands? Really, Sophie?” She sounded just like—Bahorel, Bossuet, Joly, take your pick, any one of them arguing cheerfully across a café table. Was it too much? Musichetta wasn’t sure herself. But after a second or two Sophie began to laugh. After that, Musichetta and Jeannette sat behind the counter and sewed while they waited for customers. Jeannette turned out to be a clever knitter, impatient with embroidery, cautious in the kitchen, a strong reader and orderly with figures. —- (Sophie laughed. “Really? Bahorel thought they could ask you to—what, sneak a print job through here without my knowledge? Or was the theory that if Joly asks you to do it it’s not the same as Bahorel asking me?” “Something like that. I didn’t realize you weren’t speaking at the moment.” Musichetta swirled her chocolate and blew on it before taking a long sip. Milk foam scudded across the top. “He would make either a brilliant lawyer or a terrible one. It’s a pity he doesn’t bother with studying.” “You know all about that. There’s no way to work decently within the current legal structure, no matter how many widows and orphans he defended he would only be supporting a corrupt—” “Yes, I know.” “…I see what you just did, Musichetta. Appealing to my essential solidarity with his political views.” “I promise you I wasn’t. I wasn’t doing anything. I just think Bahorel is funny and like to tell you so. —I said they would have to wait till tomorrow, I didn’t tell them yes or no.” "Them?” “Enjolras came as well.” “Good heavens. In the middle of all our fashion plates?" "Mmhmmm.” They contemplated the problem. “They probably think I’m holding a grudge over hurt feelings. Their political club declined a joint pamphlet with my political club—‘the time for women’s suffrage has not yet come’—and surely a woman couldn’t choose to separate her professional and political sphere from her romances.” Musichetta had little to say to this: this was Sophie’s realm, busily teasing out problems, talking about professional and political spheres, putting names to them. “What do you think?” "Um?” The question startled her out of her contemplation of hot chocolate and personalities. "Oh. Well—I think it’s a paying job, and we can trust their discretion. And at the moment there aren’t so many printers ready to put out anything contrary to this Martignac. I suppose he’s bought back some goodwill by freeing up the press, but…" “But it’s just a sop. Oh, I do hate a moderate!” Musichetta smiled into her chocolate. "Well. We’ll do it, then. If you are asking me. Because, you know, we don’t have any agreement against mingling our political spheres, you and I.” “You make it sound like something shocking.” Musichetta was not sure that she herself had spheres. What would you even call her political sphere? Her professional sphere? The word began to sound foolish when you said it too many times. Still, the two of them ended up in agreement often enough, she and Sophie— “Shocking will be Bahorel’s swagger when he decides his clever scheme has paid off.”) —- Musichetta waited a full year to open the trunk from Joly. Mostly it held books. There was a sketch of her sitting at a window that looked as though the (perfectly correct and respectable) anatomy ought to be labeled. There were some pressed flowers that she thought were ones she collected on a picnic. There was a blue enamel brooch set with tiny chips of garnet and diamond; under its glass dome lay a curl of glossy black hair. She pinned it to her dress before she could think too much about it. And of course a letter. She slit the envelope with her penknife, again before she could think too much about it, and spread it on the desk as firmly as if it were a bill. And then frowned. It was Bossuet’s handwriting. My very dear Musichetta, Joly is such a fretful fellow. I’ve seen him write you dozens of love-notes, frowning and sighing and re-arranging his hair like a much more appealing Byron, but this one he says he can’t write. It was the same in 1830. (We burned that letter, by the way, and I dare to hope we’ll burn this one as well, unseen.) He is trying to dictate something and tangling himself up in a description of your many virtues and charms. At the moment I’m not sure whether he means to say that you have hair like a dawn goddess’ and feet like the night sky, or the other way around. I trust you to know how to take this. If you open the books you will find something practical tucked between the pages. Joly is terribly apologetic about it: he thinks it insufficiently romantic, and yet he’s the one who has saved it up and recommends that you invest it sensibly. I refrain from advising you on your finances. Do whatever you think best, which I’m sure is whatever I wouldn’t do. (Oh, I’ll advise anyway: spend it at once on hats and cakes and wine. Be like one of those laughing young widows with rosy cheeks and dimpled wrists and low-cut dresses.) Now he wants me to write about the Republic. Well. That is something surer than a goddess’ tread and more beautiful than the night sky, and I think you admire it well enough yourself not to be jealous that your foolish young men turn their heads to look its way. After all, we do mean to bring it back for you to meet. My only complaint about losing my hair (hush, my only real complaint) is that I can’t leave you any elegant locks in tricolor brooches. Remember me kindly even so? I am your madly fond Lègle (de Meaux) P.S. I have taken the pen from Bossuet after all. I won’t read what he wrote, as a mark of trust. Musichetta, I think I would have been a good doctor. With your love I would certainly have been a happy one. —Bossuet tells me he has given you my advice about the money, but you know better about these things than either of us. Be comfortable, be happy? Your Joly — She told Sophie about it in bed that night. (They had shared a bed a year ago at the time of the barricades, for comfort, and then from habit. Now and then they made tentative jokes about being an old married couple. Or a young married couple, Sophie said once, raising her eyebrows and fixing Musichetta with her level gaze. It was a conversation Musichetta thought they might continue—a little later. When they were ready to put away their grey dresses and black ribbons.) “Did Bahorel leave you anything like that? Letters, or something to remember him by—?” “Oh, no. No. That wasn’t his style. And things were different with us, I think.” “Different how?” She did her best to keep the asperity out of her voice. Sophie had always seemed amiably amused by Musichetta’s romantic life. (She had reminded her of Bossuet that way, which was an odd thought that Musichetta put away at once.) “There was never any idea of marriage.” “Joly and I never—” “I know, I know. Community living, free love, a little Fourier, a little Saint-Simon, you and Joly and L’aigle de Meaux—I’m not laughing at you.” Musichetta was unprepared for the sudden softness in Sophie’s voice. She was stroking Musichetta’s hair. “I’m not, not even a little. We were all of us very happy. —What will you do with the money?” “Mmm. A steady modest income for my old age. That’s for half of it; and we need either to put more money into the printing end of the business or to give it up altogether and keep to selling fashion plates.” “Oh we do, do we?” “Yes, with two more presses we could—” “Two more presses!” — 1868: These days Sophie read her mail sprawled on the sofa, wrapped in a dressing-gown and smoking. Her old print of Toussaint Louverture hung over her left shoulder; it had been joined on the right by a photograph of Alexandre Dumas. (Once she had come home with a copy of a sketch of the same author as a young man, draped elegantly on a not-dissimilar sofa. It had cut through Musichetta’s heart. The photograph was easier to live with: older and heavier, he didn’t look so very much like Joly.) So: Sophie, draped not-at-all elegantly, smoking, flicking lazily through a pile of correspondence. They had been out of town for three weeks, the annual visit to Musichetta’s sister. Now it was time again for home, and the print shop, and Sophie-on-the-couch-reading-mail. The bills she passed to Musichetta with a shudder. It was their system. Musichetta tapped them neatly into a pile at her elbow as they arrived, and kept knitting. Personal letters came next, once Sophie had separated out the tedious bits of business. Most came addressed to Sophie, these days. It had bothered Musichetta until she realized that their friends were simply writing to them both, a couple under one convenient name. After that they had refined their system, and simply divided all piles of mail in half. Once the bills were sorted out. And letters. Sophie passed over Musichetta’s share; she put down her knitting long enough to pick out the briefest ones to skim through. Invitations to dinners already missed. Have you read the latest article by S—-? Did you know that G—- has had her baby? Invitations to dinners yet to come. Would they be interested in learning about an extraordinary new formula for printer’s ink, guaranteed never to fade? Invitations to lectures and poetry-readings. “Are we engaged the evening of the twenty-third? It’s a Tuesday.” Sophie stared at her blankly over the top of her spectacles. “How would I know?” “Some people do things like remember their social engagements.” Her only answer was a snort. When Musichetta came back from collecting their calendar-book Sophie was sitting straight up. She had refilled her pipe and was drawing on it in vigorous little puffs. Smoke mingled with her braided hair, the same shade of grey. “Musichetta—” “Mmm?” “André Léo wrote us.” “…And?” You didn’t just say André Léo wrote us, you said André Léo wrote us and wants us to push the limits of current laws regarding the liberty of the press. Sophie was trying to look casual. “Well, she’s planning a new novel. Perhaps you’d like to read about it.” “……And?” “It’s about a woman who disguises herself as a man to escape marriage.” “Very good, and?” "And, ah—hm. She had an idea for a manifesto. It’s called, um. Communism and Property.” Sophie peered over her glasses again, this time with her eyebrows knotted pleadingly. "She thought we might print it.“ Musichetta pinched the bridge of her nose. “Is it very illegal?” -- source link

#midsummerminimis#les miserables#musichetta#death mention#grieving#needsmoreresearch#nisiedrawsstuff