paxvictoriana: International Workers’ Day: ‘The Great Upheaval’ to the ‘Triu

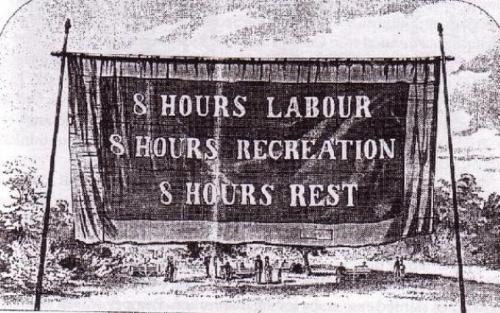

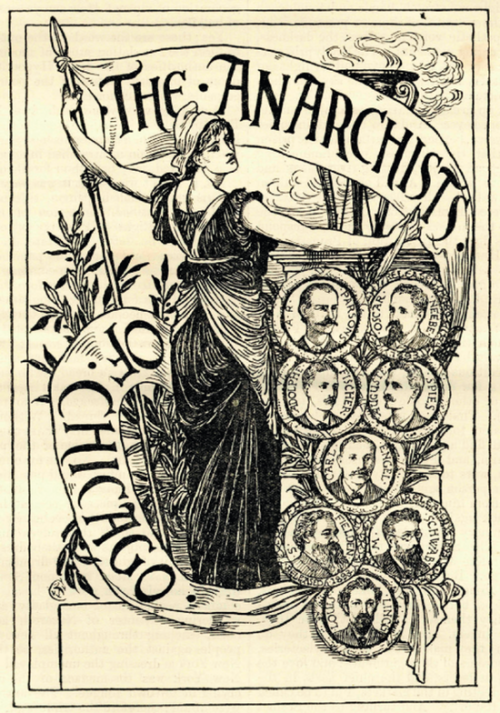

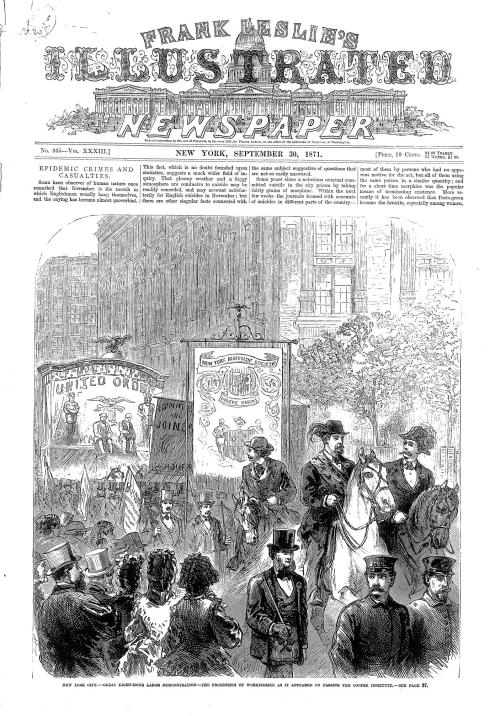

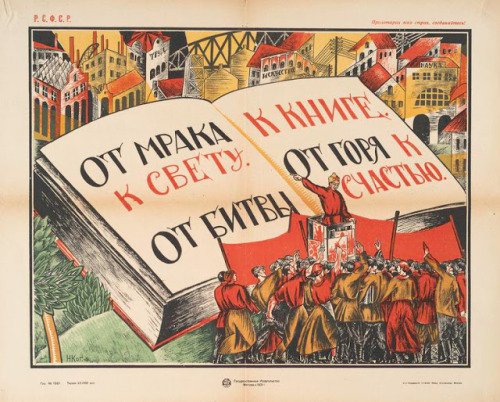

paxvictoriana: International Workers’ Day: ‘The Great Upheaval’ to the ‘Triumph of Labour’ The first of May has long been a day of celebration – whether of the arrival of spring or of religious festivities – and, since 1886 at least, been known as International Workers’ Day. Here are some images to give an abridged history of how this day became a rallying cry for political solidarity among the world’s workers: ‘8 hours labour, 8 hours recreation, 8 hours rest’ [image 1, banner; image 3, modern art comic by © Ricardo Leavins Morales; image 5, fron page, Frank Leslie Illustrated Newspaper (30 Sept. 1871), depicting NY’s “Great Eight-Hour Labor Demonstration”].The top illustration (from Melbourne) summed up the demands of workers’ strikes during some historians have called the great upheaval, a period towards the end of the 19th century when radical groups including socialists, union organizers, and anarchists became increasingly vocal and demonstrative with their calls for better conditions and terms for workers. Chicago, among other cities, was a maelstrom of these forces clashing with police, politicians, and bosses.On May 1, 1886, after months of deadly confrontations and years of simmering conflict, a group of unionized furniture workers urged other union members across the city in a walk-out: what they got was a march of roughly 100,00 workers and others in solidarity (estimates of the number differ widely, some saying close to half a million at the day’s peak). Across the country at the same time, workers’ strikes and marches were occurring too, particularly around strong radical populations as in New York, thus marking the first multi-city mass march in American history. The Haymarket Sq. Rally [image 2]: a few days later, after several days of growing unrest and demonstrations at which multiple protestors were killed in police encounters, a rally for a largely German-ethnic workers’ group gathered to hear several militant anarchists, including newspaper man and upholsterer August Spies, who was speaking when everything went incendiary.A bomb went off just in front of several mounted policemen who had arrived to jeer and instruct the disassembly of the rally – the frontmost officer was killed. From there, all hell broke loose: policemen fired on and swung batons at the crowd – and whether they fired twice or just the first time in the chaos was a matter for the trial afterwards – while reports differed on whether anyone in the crowd fired in return or, as Spies insisted, they were unarmed [x]. In the end, officially two workers were killed, though the number of casualties who were able to escape the Square but who may have died from their wounds without seeking official medical attention is impossible to know. A further five policemen died from their injuries, though one police officer anonymously told The Chicago Tribute that much damage was done by police firing on each other in the dark, chaos, and sudden smoke. The Haymarket Martyrs [image 4: ‘The Anarchists of Chicago’, by Walter Crane] Following the rally, the mayor arrested seven known militant radicals, including Spies, Adolph Fincher/Fischer, George Engel, Samuel Fielden, Oscar Neebe, Albert Parsons, Louis Lingg, and Michael Schwab (many of whom worked for Arbeiter-Zeitung, the dual English and German radical newspaper), and sent them to trial. in the end, the jury – who all testified before the trial began with some degree of prejudice against the defendants (who were tried in a group rather than individually) – convicted the 7 men of the bombing and resultant policeman’s death. Two had sentences commuted (and seeing his appeals fail, Lingg had killed himself rather than be executed), but on 11 November 1887, Spies, Parsons, Engel, and Fischer were hanged. Their deaths became seen by radicals and aggrieved workers worldwide as martyrdoms to the cause; in 1893, the then-Governor declared that the 1887 trial had been a shameful miscarriage of justice, and released and pardoned the men still in jail. Since the 1886 May Day marches, strikes, and subsequent struggles, workers have continued to use the holiday to highlight the ongoing plight of working people across the globe. Famously, the Soviet revolution in Russia made May Day an official worker’s holiday, which led, over the course of the USSR’s history (and later also, Maoist Chinese), to a deep irony of the propagandistic and increasingly sunny imagery of Soviet or Communist posters for May Day in contrast to the actual conditions of the proletariat in those countries. [Image 7, for example, shows some Soviet stamps from 1989 celebrating May Day; beside that, image 8 reads, "Ot mraka k svetu, ot bitvy k knige, ot goria k schast’iu [From darkness into light; from Battle to Books; from Misery to happiness]”, a poster by Nikolai Kogut (Moscow, 1921). Image 6, on the other hand, shows a poster using the familiar imagery of the female worker, barefoot and in nondescript dress, waving a red flag – here to celebrate the German institution of International Women’s Day, 8 March 1914.] Lastly, image 9 is the high-def panorama illustration of Walter Crane’s 1891 “The Triumph of Labour” [via Morna O’Neill]. As O’Neill describes,“Crane created his most famous commemoration of the socialist May Day celebration, The Triumph of Labour, in 1891 (Fig. 5). It would become the definitive image of English socialism. Borrowing slogans and emblems (such as the Phrygian bonnet) from the French Revolution and English trade unionism, the cartoon celebrates the unity of industrial, agricultural, and artistic labour rendered as the happy progression of liberated workers through a setting of natural bounty. The cartoon brims with decorative emblems (from the cornucopia of Lady Bountiful to the banner carried aloft by the labourers) executed in Crane’s rich linear style. It does not have recourse to the modern idiom of the newspaper or the usual political-cartoon arsenal of satire, parody, and caricature. Rather, it is a revolutionary expression of the ideal future through what Crane termed “succinct, emphatic, or heraldic expression in rich, beautiful, and symbolic form” to embody “social ideals” (Crane, “Art and Character” 114). These decorative forms embody political ideals: The Triumph of Labour is an emblematic rendering of the future promised by the hope of socialism and the central place of art in articulating and realizing that future. Rich with allusions, dense in imagery,The Triumph of Labour is a compendium of Crane’s artistic practice. At the far left, signalling his faith in the intertwined nature of art and labour, he portrays himself holding aloft a palette and riding beside an architect in a wagon bearing the standard “Wage Workers of all Countries Unite.” According to G. K. Chesterton, writing in 1912, socialists recognize each other “on the fact that a man of their sort will have … Walter Crane’s ‘Triumph of Labour’ hanging in the hall” (142). For Crane, all art—whether painting, design, decorative object, or political cartoon—constituted a better, more beautiful world that implicitly and, at times, presciently condemns the current one. Crane’s art expressed the revolutionary power of creativity and beauty, and gave voice to his hope for a better world.” [x] -- source link

#workers#labour#socialism#solidarity