recycledmoviecostumes: Goodness do I have a treat for all of you today. Larry McQueen, owner of The

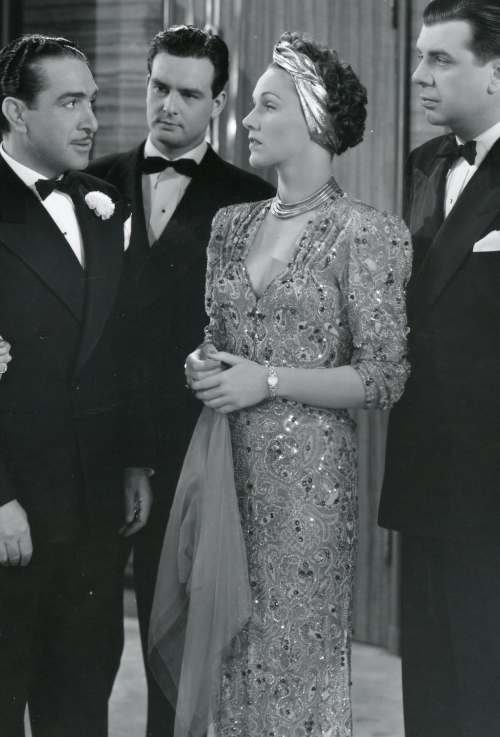

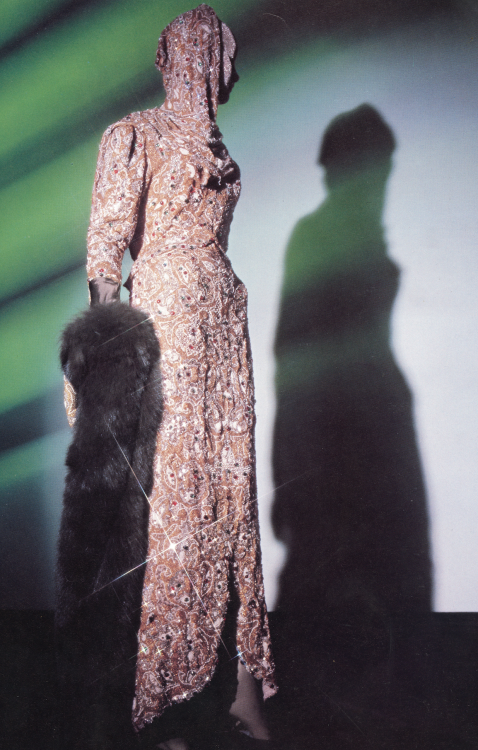

recycledmoviecostumes: Goodness do I have a treat for all of you today. Larry McQueen, owner of The Collection has sent me a lovely sighting filled with detailed information. Because the detail is frankly incredible, I decided not to edit it and present Larry’s notes in full below:In 1936, Travis Banton, head designer at Paramount Studios, began work on the last film he would design for his favorite clotheshorse, Marlene Dietrich. The duo had worked closely together on all her films at Paramount and created the “Dietrich style”– a look of lavish, smoldering, hard-edged sophistication that was instrumental in creating the Dietrich legend. Dietrich had one final film to complete her contract at Paramount and was cast in a typical Dietrich vehicle Angel, a sophisticated Lubitsch melodrama with her in the role of an ignored wife of means who has an affair with her husband’s friend. Banton designed the most opulent dress he had ever created for the star for the under-five-minute opera sequence and preceding scenes in the film. The ensemble was to become known as the “Faberge” gown and consisted of a fitted long-sleeve bodice with peplum, a matching long skirt with train and a six foot stole bordered with sable. The fabric was solidly embroidered with gold beads, pearls, rhinestones, gold bullion, gold sequins and faux ruby and emerald stones in geometric designs. According to W. Robert Levine in his book “In A Glamorous Fashion,” the costume was cost-listed on the wardrobe records at $8,000.00, an exorbitant price in the post-depression era and a price that would be over $100,000.00 by today’s standards. The expense must have caused stirrings in Paramount’s upper management in a time when the government was asking the studios to scale back the unnecessary lavishness in costume design. Banton himself once said it was the most expensive gown he had ever designed. The ensemble is given credit in many film costume books as the most spectacular gown ever created. Diana Vreeland, one-time curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art said of the costume in the book “Hollywood Costume– Glamour! Glitter! Romance!” “When I think of detail, I think of Travis Banton’s marvelous beaded dress for Marlene Dietrich in Angel—like a million grains of golden caviar. That is one of the most beautiful dresses ever…”. Margaret J. Bailey in her book Those Glorious Glamour Years describes the dress “It was simple in lines, of Persian design, and looked like a piece of woven jewelry…” and “… caused no little trauma on the set when producers refused to give it to Dietrich for her private wardrobe.” Dietrich had loved the gown and asked the studio if she could keep it. It is said she was so angry of being refused by the company she help save, she stormed off the set. The incident no doubt added to her disharmonious departure from the studio. She left the studio and did not return until a decade later. Acquiring gowns and props from her films- by whatever means- was a general practice of Ms. Dietrich. After her death, The German Film Archive Foundation (die Stiftung Deutsche Kinemathek) and The Berlin Film Museum acquired her estate in 1993, which consisted of five different storehouses in Europe and the USA. In the collection were thousands of items from her career including fifty of her most famous film gowns. Her daughter, Maria Riva, once told the curator of the Frankfurt Film Museum, her mother was always in constant fear the studios would someday try to take back her collection and had kept the fact of its existence well hidden.Paramount, however, retained the piece and began to put it to use. Re-using costumes was a common practice by studios to maintain an opulent look to secondary and background characters without the expense of making new ones. It is unknown exactly how many films the Dietrich gown was used in, but from photos found, it is obvious it was put to work and went through many transformations in the process. Mary Astor wore it, without the stole on the set of Midnight, 1939. The front was reworked and worn by Rose Hobart in the film A Night at Earl Carrolls, 1940. It was used in publicity photos as in that of Loraine Day circa 1944. With the sleeves removed, the stole without the fur was added to the front of the bodice as draping, it was worn by Felicia Atkins in The Errand Boy, 1961. The stole was cut in half to be used as a turban and worn with a sleeveless altered bodice by a model in A New Kind of Love, 1963. In 1974, the bodice was put back together and used by Diana Vreeland in the MET exhibition of films fashion and in 1985, the gown and stole was returned to its original configuration and worn by Barbara Hershey in the TV movie My Wicked Wicked Ways.With all the different uses, the pieces took a beating. Many of the “re-workings” were fast and crude and some of the attempts to repair the gown involved covering damaged areas with large gold sequins. One previous ‘restoration’ involved applying glue to areas and pushing the beads back together and letting it harden. The fine chiffon backing was weak and starting to split and the patterns were separating. The costume was so fragile, it could never be worn again, but it is amazing the pieces stayed together.In December of 1990, Paramount put the gown up for auction at Christies New York as part a larger collection of ‘star wardrobe.’ Larry McQueen and his late business partner, Bill Thomas, who were respected experts in the field of film costumes and had compiled one of the finest collections of the medium under the name “The Collection,” were retained to help inventory, authenticate and price the collection and were overwhelmed to see, what they believed to be, the most exquisite film costume ever created. They were successful in purchasing it for a total cost of approximately $23,000.00, one of the highest prices at the auction. As excited as they were to own the gown, the reality of its condition soon set in. Due to the age of the garment, poor storage and multiple alterations, it could never be dressed on a mannequin because it would not support its own extreme weight. In 1999, four years after Bill Thomas died, Larry McQueen began the process of restoring the costume. Museum experts in preservation and restoration were consulted and much debate occurred as to whether the integrity of the gown- however poor that integrity was- should be tampered with. It was finally decided by Mr. McQueen that instead of leaving it as it was- a box of un-showable beads- the ensemble should be restored. Getson/Eastern Embroidery, who was then owned by Annie Dernderian, was approached with working on the gown. The firm had worked on the original costume and luckily had many of the beads, sequins and stones used on the original construction.But, restoration of the garment proved far more difficult than planned. Even though the gown had only taken weeks to create, it would take years to restore. Every inch of the beadwork would have to be attached to new chiffon backing and the patterns pulled into shape and lightly tacked. Then the patterns had to be permanently hand stitched, replacing any missing stones or beads. Previous poor repairs would have to be removed. Missing areas or areas that had been glued would have to be replaced. Many of the original silk threads that attached the beads were breaking and would have to be reinforced with new silk thread. The stole, which had been cut in half and then stacked on top of its self and re-sewn, had to be taken apart, attached to a new backing and the beading attached and corrected. Photographs of Dietrich wearing the costume were enlarged to determine what was an original pattern and what had been changed. Luckily, the patterns did repeat themselves, so where a pattern was missing, a template of an existing pattern was made to re-create the missing one. The task would involve going inch by inch and would involve thousands of hours and great expense. But, determined to see the gown restored, Larry McQueen had the work begun.The gown could not be taken apart and beaded flat as it was originally constructed, so a special frame with a sling had to be constructed to allow access to the inside of the garment to work from the front and the back of the fabric. Beads and sequins that had to be removed were sorted and reattached in to same location if possible. Only a four-inch area could be worked on at one time and each area was photographed before and after to document the work done. The project was daunting. The entire fabric of the costume is composed of repeating geometric shapes somewhat like a paisley pattern. Each shape is outlined with small pearls or faceted rhinestones. Beads, pearls or sequins in different combinations fill the center portions of the design. Throughout, are patterns that contain a small grid work of bullion threading and each square filled with small pearls, sequins or a combination of sequins and gold beads. The background is of solid gold rocaille beads and the gown is sporadically studded with emerald and red glass beads. Literally millions of beads were used to create the fabric of the ensemble. After one year, only the bodice was approaching completion, most of the work done by Annie Denderian. But the expense was mounting and it was becoming impossible to find qualified people who had the patience and time to spend on the garment. Mr. McQueen decided that if the costume was to be completed, he would have to take over the bulk of the hands-on restoration. Having the background and more importantly the motivation to see the gown completed, he was mentored by Ms. Denderian, learning and perfecting the techniques to painstakingly re-attach the patterns and began work on the dress. Almost one year to the date of beginning the work- working faithfully five to eight hours a day- the skirt and the stole were completed. To add strength, bias tape reinforcing and a new silk chiffon lining was added by the costume house of John David Ridge and the stole was re-bordered by using existing sable by Judith Moss at LA Fur Center.McQueen stated that he probably would have reconsidered restoring the gown had he know the time, patience and expense it was going to take, but then quickly adds that he would have done it anyway. It was just too important. In working that closely with the piece, McQueen was amazed how in touch you get with the people who originally created the garment (a process difficult to understand unless you have restored someone else’s creation). You could tell when someone was having a bad day and cutting corners. You could tell when someone was struck with genius. You could see the differences in workmanship and technique between the various beaders. You could see the time spent on details in areas that no one would ever see. You become very close to the garment and understand it.The gown is truly a testament to the artistry of early Hollywood. Mr. McQueen is confident the care, attention and over 3000 hours spent in its restoration would make its original creators proud. He hopes that if he leaves any legacy to the field of film costumes, one of his main accomplishments will be the “Faberge gown” survives in the splendor it was originally created and will be shown and appreciated for generations to come.Costume Credit: Photos, copy and all the above incredible info provided by The Collection of Motion Picture Costume Design: Larry McQueen E-mail Submissions: submissions@recycledmoviecostumes.comFollow: Website | Twitter | Facebook | PinterestNote: If you’ve not checked out Larry McQueen’s The Collection, I highly suggest you do so. It’s incredible! -- source link

#marlene dietrich#travis banton#costume porn