Meet a thrust faultThrust faults are the key feature that helps build mountain ranges. Whether you a

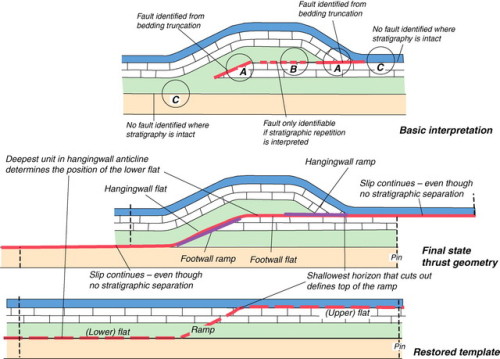

Meet a thrust faultThrust faults are the key feature that helps build mountain ranges. Whether you are walking through a modern mountain range like the Himalayas or an ancient range like the Scottish Highlands, those mountains grew on thrust faults.Thrust faults are fractures in rock units that take lower, older rocks and push them up on top of younger rocks. This setup often results in “repeating of units” as shown schematically in the diagram of a thrust fault in this post. Going vertically in the center of the image, the “green” unit repeats – it is there twice, once below the fault where it was originally deposited and again above the fault where it has been thrust into place.Thrust faults accommodate shortening of layers in the upper crust. These layers started as sedimentary and metamorphic units, with the layering inside them almost flat-lying. Something started squeezing these units from the side, causing them to fold, buckle, and then fracture. When the rocks fracture, the lower rocks are squeezed upwards along a ramp until they find another level where they can spread out. The rocks slide over the upper layer as a thrust sheet – literally flat-lying rocks with a fault in-between. The lower image in the schematic shows a “balanced cross section” - a geologist has calculated the thicknesses of the layers and used those meausrements to reconstruct the original position of the layers prior to motion on the thrust faultThe outdoor picture shows a thrust fault near Glencoul in Scotland. The upper part of the hill is Precambrian metamorphic rocks above the Glencoul thrust fault, just below the fault sits younger, Cambrian sandstones that have also been metamorphosed. The fault itself almost looks like it is in the sedimentary sequence. The most prominent layer in this sequence, which dips a bit off to the left, is the Cambrian quartzite. The fault surface sits at the very top of this prominent outcrop, and the more mossy area on top is the overlying gneisses. In this site, the fault literally sits at the top of a flat layer; the older gneisses ramped up to the east and then spread out at this flat level.This fault links into the larger Moine Thrust fault sequence that forms much of the Scottish Highlands. That fault system has, in places, accommodated over 100 kilometers of motion across it. In other words, the rocks above that fault have in places been moved horizontally by over 100 kilometers.-JBBImage credits: https://flic.kr/p/nToF8dButler, 2010: http://sp.lyellcollection.org/content/335/1/293.short -- source link

#fault#geology#thrust fault#nature#scotland#landscape#travel#glencoul#moine thrust#orogeny