nervousacid:One of the first classes I took in graduate school was a practicum for teaching college-

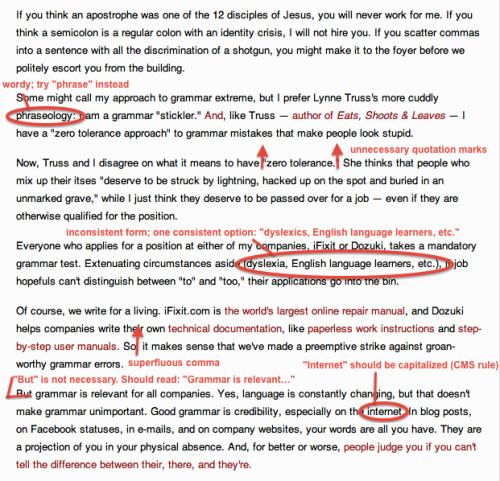

nervousacid:One of the first classes I took in graduate school was a practicum for teaching college-level composition. Every semester, dozens of grad students take this class with the hope that, when it’s done, they’ll get the chance to teach the undergrads at our university how to write. Because, come on! How else are we supposed to share our superior knowledge about the English language with these neophytes? We, the recipients of ones of twos of bachelor’s degrees! We, the authors of ones of twos of papers examining the protofeminism of Flaubert! We, the vigilant guardians of grammar, determined to thwart such foolish rogues who dare end their sentences with prepositions! Surely the English-speaking undergraduate classes of the future will fail to perfect our language unless we intervene.I wish I were joking, but that kind of discourse — a seemingly endless tirade of hyperbolic save-our-children screeds — was, much to the class instructor’s chagrin, increasingly typical of our classroom discussion. Whenever she said, rightly so, that the predominant faculty of good writing is good thinking, any number of students felt compelled to interject: But what about grammar and punctuation?“It’s a problem when it interferes with meaning,” she replied simply.When you’re coming from a purely theoretical position, this is a difficult idea to wrap your head around. But unlike many of my classmates, I’d already spent two years working with adolescents on their writing, and like most anyone with English classroom experience, the instructor’s point became quickly and painfully clear: Grammar follows meaning — not the other way around. In other words, it is entirely possible to write with perfectly constructed grammar and still be a shitty writer. It is also quite possible to be grammatically challenged and totally brilliant. The successful outcome of a composition class is, therefore, to see an increase in critical thinking, which hinges on a student’s ability to develop and organize ideas and arguments. Grammar is a tool we use in the articulation process, but it is not the singular goal — nor is it a foolproof indication of a person’s work ethic. Following the rules for the sake of being pedantic is not the mark of a good writer, but that of a good rule-follower. These are not the same thing.Over the weekend, I came across this short essay in the Harvard Business Review blog in which Kyle Wiens, the CEO of iFixit, argues that “poor grammar” is so important to his opinion of you, that he stakes his entire hiring process on it. In fact, all of his potential new hires — regardless of position — are required to take a grammar test in order to seal the deal, and according to Wiens, there is a “zero tolerance approach” in his evaluation of your work. If you don’t know the difference between ”it’s” and ”its,” he says, you’re out.This is a novel approach, but it also invites a heightened level of scrutiny on two distinct points. In the first place, Wiens seems utterly oblivious to the fact that socioeconomic conditions play a key role in the disparity of the American education system, in which those of us with more money have access to better schools and those of us without take what we can get. One of my more grammar-obsessed classmates from that semester, for one, revealed that his high school even taught Latin. (I can assure you that mine barely taught English.) But in the second place, Wiens is also placing a premium value on English as he knows it — and he is begging for us to take a closer look at his own writing.As a college composition lecturer and former copyeditor, I felt compelled to take him to task.My intention with this exercise isn’t to say that, Wiens be damned, I am the sole keeper to the secret of the English language. That’s bullshit, and I know fully well that anyone could similarly copyedit the hell out of this website. In fact, that’s why copyeditors exist: because writers can’t always police our own writing! But that’s also a point of important distinction between the two. Copyeditors worry about grammar and usage and form, but writers worry about ideas. Wiens doesn’t seem to know the difference, and that is primarily why I took a red pen to his work.I also wanted to show that being “detail-oriented” — a characteristic that Wiens seems to cherish above all else — goes far beyond grammar. His use (and misuse) of superfluous commas, quotation marks, and hyphens, for example, is quite typical of prescriptive grammarians; they seem to think more is better when, really, it’s not. As such, Wiens is essentially creating a hierarchy of prescriptivism where certain details are more important than others, and that alone is proof that this whole thing is tenuously arbitrary. If you’re making an argument like this, you need to be consistent across the board.So when I decided to evaluate this essay with a letter grade, I used an averaged score based on both of our two totally competing rubrics: Wiens’ own “zero tolerance approach,” in which he decidedly receives an F for numerous punctuation and usage errors, and my own “meaning-above-all approach,” in which I appreciate his form, but knock off a considerable amount of credit for his badly argued thesis — which falls short of actually providing any real evidence that his grammar test is anything but a ruse to perpetuate the dominant fiction of a “proper” English.The devil is in the detail, indeed. -- source link

#grammar#linguistic prescriptivism#applause#accurate#quote