oikabooks: “ My aunt also had a girlfriend. Supposedly this aunt swore to me in my cradle that I wou

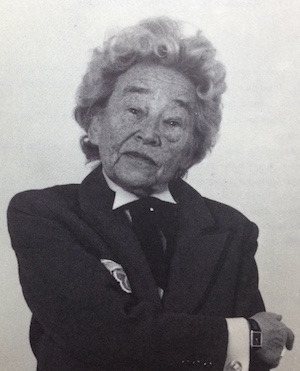

oikabooks: “ My aunt also had a girlfriend. Supposedly this aunt swore to me in my cradle that I would turn out like her. Even as a child I preferred pants and a boy’s haircut. I didn’t want to wear dresses and skirts. When I first started working at AOK, I had to run errands and get files from the basement. There was always a group of women in the basement sitting, singing, and dancing with each other; I’ve always loved to dance. Sometimes they had a bottle and we drank a bit. It was there that I saw Hilde Berghausen, and I thought to myself “Gee, you could fall for that Hilde!” But I still didn’t really know why. Hilde was older than me; I was fifteen and she was twenty or twenty-one. Once she invited me home with her; I went with her—brought a pounding heart and a bouquet from our garden with me. Her parents were on vacation. We were talking and she asked me if I had a girlfriend. “Of course. Herta, my friend from school.” “There are two kinds of girlfriends.” “What do you mean, two kinds? I really love Herta!” […] I started going to the clubs and got to know everything around 1931, when I was fifteen. Back then, before Hitler came to power, we had a lot of clubs. For example, at the Andreas Festival Theater on Andreas Street there was a ball once a month. Through the Magic Flute, I joined a lesbian bowling club, “The Funny Nine”, which was led by Lieschen and her girlfriend Gertrud. We went bowling once a week, and once a month we rented a really big room in a dance hall on Landsberger Street. It was really nice, young and old together, fifty- to sixty-year-olds, the rest around twenty, and I was always the youngest. Later, after 1933, the proprietors–they were Nazi supporters–they stopped renting to us. Lieschen, who was in her sixties then, said “Let’s just forget this club.” And so we just forgot about it. I also went to the Monocle Bar…I still remember a lot of women who frequented that club. But they closed the Monocle Bar in 1933. […] When I went back home after the Labor Service, my mother found out, since all my girlfriends had written to me. I had stolen chocolate and cigarettes—we had everything in the restaurant—and I sent all my sweethearts little packages and they wrote, “My dear little Johnny-mouse, thanks so much for the wonderful package. I’m lying on my bed smoking a cigarette from you and I think of you always. Oh, I wish you were still here with me!” When my mother saw all the letters she thought “Oh my goodness, that isn’t normal; there’s something not right here.” Every day four or five letters arrived. […After the official ban on homosexual clubs,] outside it always said “Private Party.” You had to ring a bell and she only let in people she wanted. In 1941 there was also a very nice club on Hoch Street… but that one closed suddenly too. Even during the Nazi period there were always clubs you could go to, but they always disappeared again after a while. After 1938 there were more and more raids. If we went to one and it was closed, then we didn’t know what had happened. Before the war, Lotte Hahm had also opened a place, at Alexanderplatz in the teacher’s association building on the second floor. There used to be a dance café there. Lotte Hahm had rented it and organized ladies’ nights there. But that didn’t last very long either. […] I knew that Lotte Hahm served time in jail for seduction of a minor. That’s just nonsense; I’d never believe that about her. It was just a pretext. Then I heard that she was supposedly in a concentration camp. She really had disappeared from the face of the earth for years, so that must be true. […] Margot and [her girlfriend Hildegard, aka] Peter, both lived with Lissy, a woman like us who still lived at home and had already hidden one Jew, also one of us. Margot was in hiding there and Peter lived there officially. […] All of a sudden [the Gestapo] came from Gesundbrunnen Station. I said to Margot, “Don’t even bother going home; come with me.” She stayed with me at least three to six months. I had a one-room apartment. We only went outside in the dark at night; she had to get some fresh air. I had really nice neighbors who didn’t support Hitler at all. Our landlady was Jewish; the landlord wasn’t, but because they were married—a so-called privileged mixed marriage—he had been able to save her. The Jewish woman was really great; she tolerated our having girlfriends, that is, this homosexuality. She was the only one who knew I had hidden Margot. The neighbors didn’t know; I never would have said anything. Back then children even denounced their own parents.[…] One evening we were at Vineta Square again and a woman from the house saw her. Margot hadn’t noticed that she was being watched. The Russians were already in Berlin, but there was still a lot of shooting. The next day the Gestapo came again—to me this time. If they had gotten her then, they would have shot her. Of course, they would have shot me too. But Margot wasn’t there; she was upstairs at Hanni’s—also one of us… When they came to check on me, I simply said “I don’t know any Margot” and they were finished with me. It was May, right before the war ended. ” —Anneliese W. (1916-1995), from Claudia Schoppmann’s Days of Masquerade: Life Stories of Lesbians During the Third Reich -- source link