The Dark Side of the CityWhat is it about Hopper? Every once in a while an artist comes along who ar

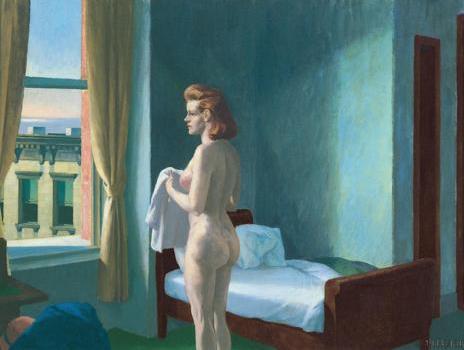

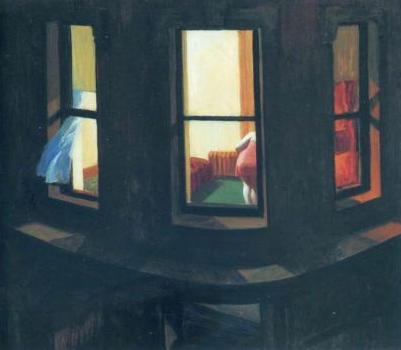

The Dark Side of the CityWhat is it about Hopper? Every once in a while an artist comes along who articulates an experience, not necessarily consciously or willingly, but with such prescience and intensity that the association becomes indelible. He never much liked the idea that his paintings could be pinned down, or that loneliness was his metier, his central theme. “The loneliness thing is overdone,” he once told his friend Brian O’Doherty, in one of the very few long interviews to which he submitted.Why, then, do we persist in ascribing loneliness to his work? The obvious answer is that his paintings tend to be populated by people alone, or in uneasy, uncommunicative groupings of twos and threes, fastened into poses that seem indicative of distress. But there’s something else too; something about the way he contrives his city streets. What Hopper’s urban scenes replicate is one of the central experiences of being lonely: the way a feeling of separation, of being walled off or penned in, combines with a sense of near unbearable exposure.This tension is present in even the most benign of his New York paintings, the ones that testify to a more pleasurable, more equanimous kind of solitude. Morning in a City, say, in which a naked woman stands at a window, holding just a towel, relaxed and at ease with herself, her body composed of lovely flecks of lavender and rose and pale green. The mood is peaceful, and yet the faintest tremor of unease is discernible at the far left of the painting, where the open casement gives way to the buildings beyond, lit by the flannel-pink of a morning sky.In the tenement opposite there are three more windows, their green blinds half-drawn, their interiors rough squares of total black. If windows are to be thought analogous to eyes, as both etymology, wind-eye, and function suggests, then there exists around this blockage, this plug of paint, an uncertainty about being seen – looked over, maybe; but maybe also overlooked, as in ignored, unseen, unregarded, undesired.In the sinister Night Windows, these worries bloom into acute disquiet. The painting centres on the upper portion of a building, with three apertures, three slits, giving into a lighted chamber. At the first window a curtain billows outward, and in the second a woman in a pinkish slip bends over a green carpet, her haunches taut. In the third, a lamp is glowing through a layer of fabric, though what it actually looks like is a wall of flames.There’s something odd, too, about the vantage point. It’s clearly from above – we see the floor, not the ceiling – but the windows are on at least the second storey, making it seem as if whoever’s doing the looking is hanging suspended in the air. The more likely answer is that they’re stealing a glimpse from the window of the ‘El’, the elevated train, which Hopper liked to ride at night, armed with his pads, his fabricated chalk, gazing avidly through the glass for instances of brightness, moments that fix, unfinished, in the mind’s eye. Either way, the viewer – me, I mean, or you – has been co-opted into an estranging act. Privacy has been breached, but it doesn’t make the woman any less alone, exposed in her burning chamber. -- source link

#asian loneliness#edward hopper