talkingpiffle:Previously: the 1481 Dante folio, the 1493 “Golden Legend.”“Thanks. I am going to Batt

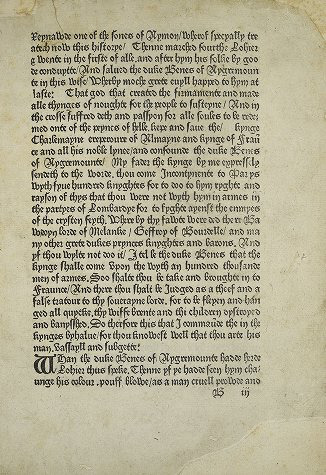

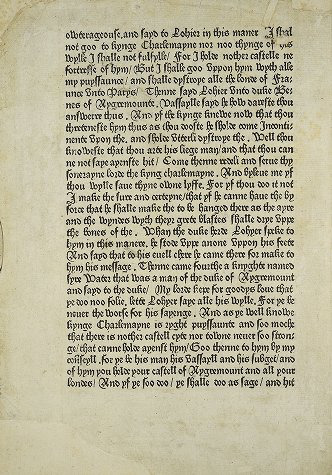

talkingpiffle:Previously: the 1481 Dante folio, the 1493 “Golden Legend.”“Thanks. I am going to Battersea at once. I want you to attend the sale for me. Don’t lose time—I don’t want to miss the Folio Dante nor the de Voragine—here you are—see? ‘Golden Legend’—Wynkyn de Worde, 1493—got that?—and, I say, make a special effort for the Caxton folio of the ‘Four Sons of Aymon’—it’s the 1489 folio and unique. Look! I’ve marked the lots I want, and put my outside offer against each. Do your best for me. I shall be back to dinner.”“Very good, my lord.”“Take my cab and tell him to hurry. He may for you; he doesn’t like me very much. Can I,” said Lord Peter, looking at himself in the eighteenth-century mirror over the mantelpiece, “can I have the heart to fluster the flustered Thipps further—that’s very difficult to say quickly—by appearing in a top-hat and frock-coat? I think not. Ten to one he will overlook my trousers and mistake me for the undertaker. A grey suit, I fancy, neat but not gaudy, with a hat to tone, suits my other self better. Exit the amateur of first editions; new motif introduced by solo bassoon; enter Sherlock Holmes, disguised as a walking gentleman. There goes Bunter. Invaluable fellow—never offers to do his job when you’ve told him to do somethin’ else. Hope he doesn’t miss the ‘Four Sons of Aymon.’ Still, there is another copy of that—in the Vatican.* It might become available, you never know—if the Church of Rome went to pot or Switzerland invaded Italy—whereas a strange corpse doesn’t turn up in a suburban bathroom more than once in a lifetime—at least, I should think not—at any rate, the number of times it’s happened, with a pince-nez, might be counted on the fingers of one hand, I imagine. Dear me! it’s a dreadful mistake to ride two hobbies at once.”* Lord Peter’s wits were wool-gathering. The book is in the possession of Earl Spencer. The Brocklebury copy is incomplete, the five last signatures being altogether missing, but is unique in possessing the colophon.–Dorothy L. Sayers, Whose Body?, Chapter I, 1923.“The Four Sons of Aymon” is a medieval French tale about four knights and their magical horse Bayard fighting against Charlemagne. The oldest extant version of the story dates to the late twelfth century. Caxton’s 1489 edition is the first known translation into English. Like Lord Peter’s 1477 Naples folio of Dante, the only surviving copy of Caxton’s folio has a mysterious provenance, according to Octavia Richardson’s introduction to her 1885 scholarly edition:The original edition of Caxton’s “Four Sons of Aymon” has neither title-page, printer’s name, place, nor date. It is a folio volume, and the fortunate possessor of the only copy known is Earl Spencer. The celebrated founder of the Althorp Library, Earl George, acquired it by purchase in the year 1822. Of its previous history we can discover nothing. The date assigned to it by Blades, in his life of Caxton, is 1489, and has been adopted from the circumstance, that the works issued from Caxton’s fount No. 6 range from 1489 to 1493. Although Earl Spencer’s copy is unique, it is not perfect. It lacks Caxton’s prologue and colophon. (x)Thus the (fictitious) edition Lord Peter seeks to purchase at Sir Ralph Brocklebury’s auction would indeed be unique. The Earl of Spencer’s copy is now held by the John Rylands Library at the University of Manchester.Images: The first two pages (after the missing prologue) of “The Right Pleasaunt and Goodly Historie of the Four Sonnes of Aymon,” translated and published by William Caxton circa 1489. (x) -- source link

#<3#incunabula#books#whodunit#queue