osvobodi:RefusalThe work Talaq by an artist from Kazakhstan Medina Bazargali is about the “triple ta

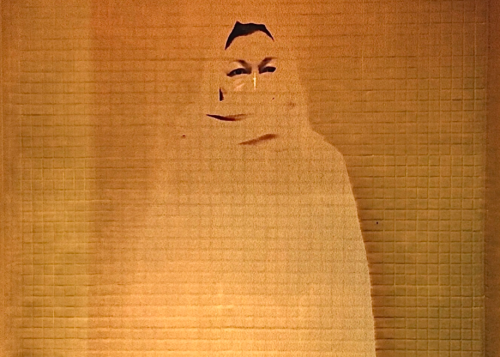

osvobodi:RefusalThe work Talaq by an artist from Kazakhstan Medina Bazargali is about the “triple talaq” – Islamic law which allows men to divorce their wives by saying “talaq” three times either in person, on the phone or simply in a form of a text message, while the only way a woman can divorce her husband is to go through a complicated system of asking for permissions. In an interview, Medina Bazargali describes the reasons of this situation “that became increasingly popular, not only as a consequence of Islam spreading aggressively in Kazakhstan since its independence but also because of the absence of age restrictions for marriage.” Therefore, she connects the existence of the oppressive practice to the way it is used by the state and supported by the local legislation.Thus this work criticizes the “return to the traditions” within the supposedly secular nation-state. In Kazakhstan reshaped traditions assert hierarchical gender relations, where the male and masculine have pre-eminence over female and feminine. “The return to the traditions” in Kazakhstan is not so different from similar processes in Russia, which tend to privilege the “traditional values” of an orthodox Christian patriarchal family. The “traditional values” are universal machines for the reproduction of the oppressive states apparatus. Medina Bazargali’s work, while acknowledging the clearly sexist nature of the practice of Talaq, emphasizes the agency of the state, which renders a woman as completely invisible the moment she gets married. The installation is interactive: once a visitor enters the space and covers her head and face with a red piece of cloth, which is of the same colour as the traditional wedding dress, she is photographed. After the photo is taken, in a picture one can only see her eyes, while the whole body is morphed with the wall. The perspective of a camera mimics the gaze of the state: it is not the red cloth that conceals a woman after she gets married, it is the algorithm inscribed in the camera, that renders her invisible. Similarly, the laws of a state (which does its best to return to the “traditions”, while rendering invisible the women, who are affected by certain traditions that are oppressive) not the abstract Islam itself. I am clicking through documentation pictures, showing only the eyes of the installation-visitors, when I scroll too fast it feels like the eyes were also bricks in the walls. Even though in this I process I occupy a position, which might seem like the one of an outside observer, my position is situated as I am repeating the patriarchal gaze, which renders a woman invisible. By making the artwork participatory, the artist refuses the viewer any outside perspective, which tends to concentrate on the images of suffering but not on what produced them.Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang theorized refusal as the turning back upon power, specifically the colonial modalities of knowing persons as bodies. Another work of refusal, according to Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang is to “set limits to settler-colonial knowledge”. Talaq sets limits to the knowledge that see Muslim women as the victims of the abstract patriarchy and does not consider the agencies of nation-states and colonialism. As Talaq shows, the refusal requires positionality and the understanding of the absence of outside perspective.- Sasha Shestakova, Hiding in a Plain Sight -- source link